The coastal regions of the Eastern Pacific are among the most productive on earth and the Gulf of California is no exception. In contrast to the open ocean, which is a virtual desert, coastal areas are highly productive, and on the western side of the Pacific Ocean they are often very, very productive indeed. Why? Because the prevailing winds that blow parallel to the land peel back the shallow coastal waters exposing rich, cool, deep waters that cause marine plants to flourish. The Gulf of California is nine times as productive as the average productivity of the open ocean.

In contrast to the Western Pacific where the waters are warm and coral reefs flourish, the upwelled waters in the Eastern Pacific are cool. Additionally, oceans currents in the Eastern Pacific flow toward the equator carrying cooler water from the poles. North of the equator in the Eastern Pacific the water is warmer due to the North Equatorial current carrying warm water across the Pacific from the west where it mixes with the cooler waters from the north and south. Therefore, the ranges of warmer-water fish and corals extend 1000-1500 miles farther north of the equator than to the south of it. Corals can tolerate water temperatures as low as 17 degrees centigrade but thrive where it is warmer and sunlight is abundant. These oceanographic factors limit the growth of corals that are present in the Gulf of California region so they rarely build reefs. Cabo Pulmo’s coral reefs are the most northerly found in the Eastern Pacific.

In addition to this, cooler temperatures decrease biodiversity. The tundra and the polar oceans have a much lower biodiversity than tropical rain forests or coral reefs do. While cooler regions may be more productive and have lower biodiversity, they often have a very high abundance of each species. This fact is critical in understanding the impacts of overfishing. If a single species is targeted and removed from the ecosystem, the flow of energy through the entire food web may be catastrophically disrupted—and when many species are reduced or removed altogether, the marine ecosystem can collapse. That is essentially what happened at Cabo Pulmo.

The stories about the following fish are chosen because they are now commonly seen and, in addition, help to illuminate the way a marine ecosystem functions.

FAMILY: Clupeidae (Herring-like fish)

FAMILY: Clupeidae (Herring-like fish)

COMMON NAME: Sardines – Sardina Monterrey

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Sardinops sagax

Description

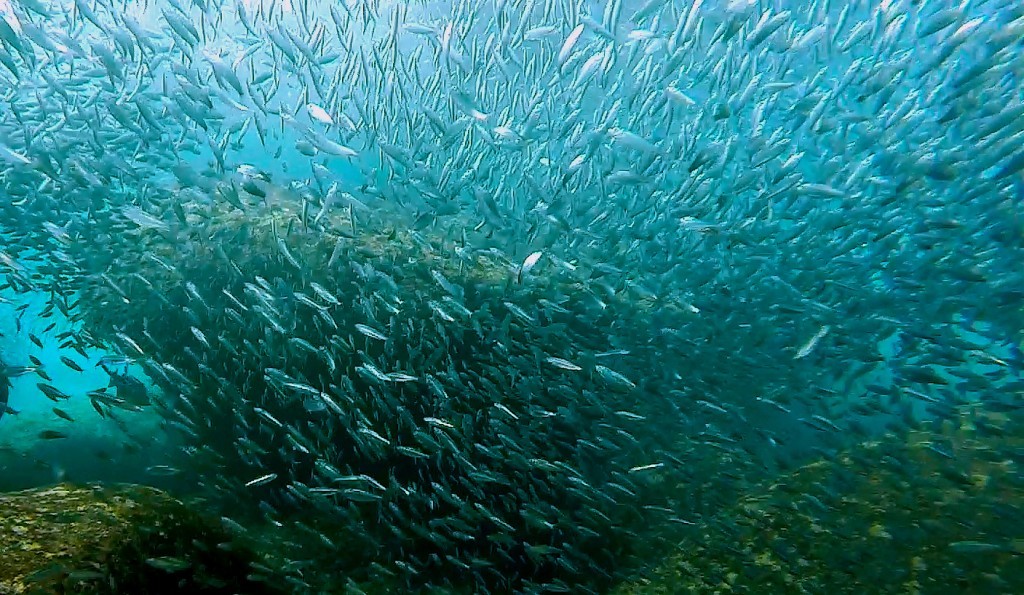

Sardines—so named by the Greeks for the Island of Sardinia—are very close to the base of the food web and are the foundation for the survival of many species. We tend to think of sardines as diminutive fish because that is the way we normally eat them, when they are small. Larger sardines are often sold as pilchards. Sardines can in fact reach a surprising 2 feet in length (39.5 centimeters), weigh more than 1 pound (486 grams) and may live to the astonishing age of 25.

Range & Habitat

This single species ranges from the east coast of Africa to Alaska, Peru and southern Chile and is described as having at least three distinct lineages, derived from populations as remote from one another as South Africa, Australia, Japan, Chile and California.

Natural History

The juvenile sardines eat zooplankton—tiny nutritious creatures carried in the currents—and by the time they mature, they have transitioned to consuming phytoplankton, which are the smallest plants in the ocean. Consequently, sardines rarely go hungry and they grow so fast that some even breed in the first year of life, usually in late winter or spring. A small female may scatter 10,000 eggs into the surface waters while the biggest females may produce as many as 60,000. As the larvae grow, they make their way inshore, migrating northward in the northern hemisphere in vast schools along the coast. The sardines are popular prey items for reef carnivores, open-water fish, birds, dolphins and whales. Some predators may depend upon the sardine migrations to fatten up enough to spawn. As winter approaches, the sardines migrate back south again. Sardines are critically important in marine ecosystems as they convert the sun’s energy from algae into bite-sized snacks for even the largest predators.

For more information:

Fishbase

Ocean Oasis field guide

Discover life

FAMILY: Acanthuridae (Surgeonfish)

FAMILY: Acanthuridae (Surgeonfish)

COMMON NAME: Yellowtail surgeonfish – Cochinito

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Prionurus punctatus

Description

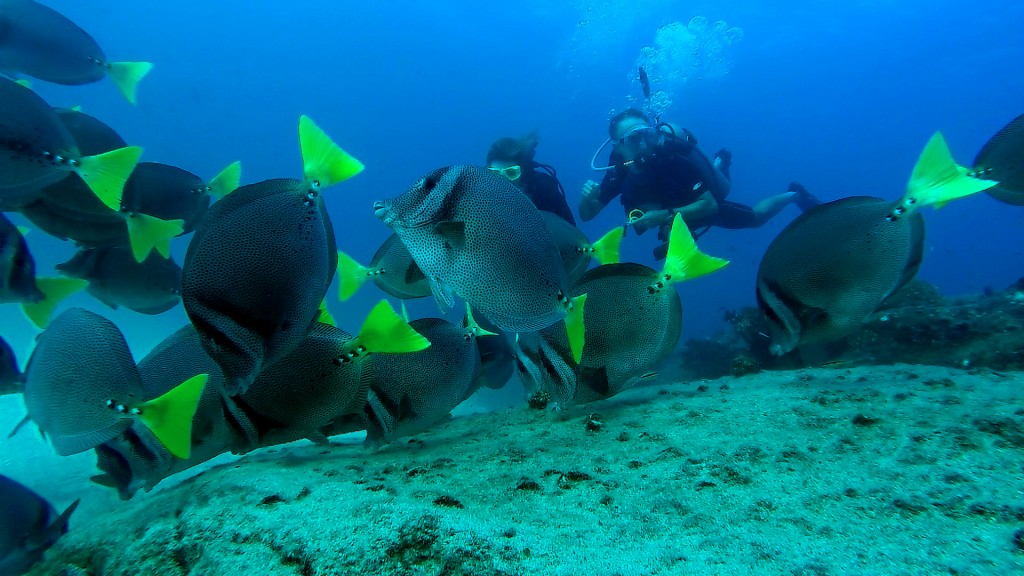

The Yellowtail surgeonfish belongs to the Acanthuridae family that includes unicornfish and tangs. As a family, surgeonfish are extremely handsome with fine scales usually dapperly adorned with beautiful patterns. They primarily use their pectoral fins for propulsion to fly through the water, and their dorsal and anal fins are long and extend as far as the tail base. The name Acanthuridae is derived from the Greek words akantha and oura, meaning thorn and tail, as all members of the family have the distinguishing characteristic of a scalpel positioned at the base of their tail (caudal peduncle). Yellowtail surgeonfish have three spurs on either side. While these surgeonfish are reputed to reach lengths of 2 feet (60 centimeters), such size is rare.

Range & Habitat

Surgeonfish are among the most abundant reef fish of tropical and subtropical waters. Yellowtail surgeonfish are common residents of shallow reefs, usually within the surface 40 feet (12 meters) and range from Southern Baja California, Mexico to Central America.

Natural History

This species, near the base of the food web, feeds primarily on turf algae that cover the rocks near the surface and sometimes range into the surf zone. These surgeonfish have fleshy lips for grasping and large, closely set, chisel-like teeth for cutting turf algae, not unlike a horse’s mouth. They can also be found supping on the feces of Chromis atrilobata, which presumably contain some vital undigested ingredient that they favor. Like most surgeonfish, they are usually social, traveling in tight schools during the day and often in the company of other species. At night they find shelter on the seafloor, often in caves.

On Cabo Pulmo’s reefs, these fish are remarkably amenable to divers. They breed by scattering their eggs over the seafloor.

For more information:

Fishbase

Encyclopedia of life

FAMILY: Pomacentridae (Damselfish)

FAMILY: Pomacentridae (Damselfish)

COMMON NAME: Scissortail Chromis – Castañeta

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Chromis atrilobata

Description

Named for the Greek word meaning fish, Chromis are found in all tropical and subtropical oceans, including the Aegean Sea. Their own subfamily is characterized by species that swim with their pectoral fins, have domed heads and deeply forked tails. While Scissortailed Chromis have been reported as long as 5 inches (13 centimeters) they are generally much smaller and live as long as 18 years in captivity. In the wild, it is thought they do not live longer than 12 years or so.

Range & Habitat

Scissortailed damselfish, or castañeta, are native to the Eastern Pacific Ocean between Baja California, southward to Peru and west as far as the Galapagos Islands. They are shallow-water inhabitants of rocky reefs and normally are found to the depth of no more than 65 feet (20 meters).

Natural History

Chromis occupy an important role at the base of the food web. All species of Chromis tend to exploit a similar niche. They live close to the seafloor at night where they find shelter, but during the day, they rise up into the water column, jigging around with their pectoral fins in dense aggregations, picking off small planktonic crustaceans wafting in their direction on the ocean currents. When danger threatens, they dive for shelter among the corals or rocks. Even in shelter, they are not completely safe from predators such as leopard groupers and moray eels that may work together to catch them. Chromis populations can expand rapidly, doubling every 15 months, so it seems probable that a variety of predators target them.

As with other members of the damselfish family, the males will build a nest to entice a female to lay her eggs on the rocky substrate, which he will guard and oxygenate until they hatch a few hours or days later. The larvae are planktonic and drift away in the currents. Only a few of the young fish will survive to find a suitable habitat to settle, usually far from where they began life.

For more information:

Fishbase

FAMILY: Scaridae (Parrotfish)

FAMILY: Scaridae (Parrotfish)

COMMON NAME: Bumphead Parrotfish – Perrico

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Scarus perrico

Description

The Greeks fished in the Aegean for parrotfish—skaros—providing the family/generic name. As a group, parrotfish are relatively sizable, garishly colored, large-scaled fish that use their pectoral fins as their primary means of propulsion. Their teeth are fused into a beak, not unlike a parrot’s, which they also resemble because of their color schemes. Bumphead parrotfish are relatively abundant on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs and are distinctive if you come across them because of the large bumps on the top of their heads.

Range & Habitat

Bumphead parrotfish are confined to the Eastern Pacific Ocean and range from the Gulf of California southward to Peru and westward as far as the Galapagos Islands. They are typically found in the surface 40 feet (12 meters) but have been observed to depths of around 120 feet (36 meters).

Natural History

Bumphead parrotfish usually occur in small groups within a home range over rocky reefs where they feed on turf algae, coralline algae and detritus. They also are reported to eat Pavona and Porites corals. Frequently, they can be heard scraping the rocks by divers before they are seen.

Most species of parrotfish have adopted the evolutionary reproductive strategy called protogynous hermaphroditism (the sex-change strategy is also called sequential hermaphroditism). This is likely the case for bumphead parrotfish, which start life (juvenile phase), destined to become fully mature females (initial). They are dominated by a male (terminal), the largest individual. It is thought that the presence of the male suppresses the dominant females’ transition into the terminal male phase. Consequently, the majority of adult individuals are females whose eggs are fertilized as they are released into the surface waters during mating, thereby maximizing the number of offspring produced by the population.

While not taken by hook and line, parrotfish are easy targets for spearfishers. Following their protection in Cabo Pulmo, their numbers increased 10-fold.

For more information:

Fishbase

FAMILY: Pomacanthidae

FAMILY: Pomacanthidae

COMMON NAME: King angelfish – Angel rey

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Holacanthus passer

Description

Angelfish are among the most stunningly beautiful marine fishes. Their family is characterized by a backward pointing spine on the gill cover (operculum) that gives the family its scientific name from the Greek poma, meaning cover, and akantha, meaning thorn. Among the showiest of Cabo Pulmo’s reef inhabitants, the king angelfish is one of three Pomacanthid species in the Gulf of California. The youngsters of this species are brilliantly adorned with bright orange scales over much of their bodies, a pattern interrupted by 10 iridescently blue vertical bars and a single white one. Their tail, pectoral and pelvic fins are brilliant yellow as juveniles but as the fish mature the orange body scales turn bluish while retaining the white bar and fin coloration. In males, the pelvic fins are white.

Range & Habitat

King angelfish are confined to the Eastern Pacific Ocean and range from the Gulf of California southward to northern Peru and westward to the Galapagos. They are a home-ranging, shallow-water, species found over rocky or coral reefs to depths of around 100 feet (30 meters) although primarily in the surface 60 feet (18 meters). The females are reported to be more territorial than the males are.

Natural History

Like most angelfish they range over the reef to feeding on benthic invertebrates such as sponges, tunicates and algae. Sometimes king angelfish occur in aggregations particularly when feeding on a locally abundant food source such as patches of zooplankton, salps, jellyfish, or on the feces of certain aggregating species, such as Chromis. They are diurnal in habit, meaning that they are active during the day and find refuge in caves or under rocks at night.

King angelfish, like most varieties, are monogamous, forming pair bonds and breeding with only one individual of the opposite sex. Since they may live for more than a decade, it is a union that may last many years. These angelfish mate around sunset on most evenings between June and December discharging eggs and sperm into the water column. Reportedly during this period they may release as many as 10,000,000 eggs. While it has yet to be confirmed, scientists believe that king angelfish may be protogynous hermaphrodites (starting life as females and becoming males later, as needed).

For more information:

Fishbase

Discover life

FAMILY: Labridae (Wrasses)

FAMILY: Labridae (Wrasses)

COMMON NAME: Cortes rainbow wrasse – Arcoiris de Cortés

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Thalasoma lucasanum

Description

The wrasse family (named pejoratively from the Cornish word wragh, meaning hag or old woman) is represented by more than 600 species of fish. While the rainbow wrasse is a typical small and colorful example of the family, certain species (Cheilinus undulatus) attain a size of more than 8 feet in length (2.5 meters). As a family, they are carnivores favoring benthic invertebrates. Their removal through overfishing can significantly upset the balance of their ecosystem. The Cortes rainbow wrasse’s name is derived from the Greek thalassa, meaning the sea, and soma, meaning body.

The largest Cortes rainbow wrasses are less than 6 inches (15 centimeters) in length and most of them on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs are half this size. Cortes rainbow wrasses are usually seen in aggregations of 30-300 animals with a smart yellow uniform in the initial stage with a white belly and a broad dark stripe that extends from the eye to the tail. Behind the pectoral fin, a red line sweeps back to envelop the tail. These individuals are both male and female in a proportion that is dynamically controlled by social pressures within the group.

In the general vicinity of this melee of colorful fish, often one or more terminal-stage male Cortez rainbow wrasses maintains and defends a territory through which the roving schools of males and females pass. The larger male, in the terminal color phase, has a vivid purple body with blue-green markings on the cheeks, a blue tail and a broad, bright-yellow saddle behind the gill covers.

Range & Habitat

Cortes rainbow wrasses range from the Gulf of California to Peru and the Galapagos Islands. They are abundant in shallow water over rocky reefs and may be found in deep water (to 210 feet, or 64 meters), albeit rarely.

Natural History

The Cortes rainbow wrasses begin as both male and female and are clad in the initial-phase coloration. Mature individuals will rise to spawn en masse and disperse their gametes into the open water, usually in summer, where the fertilized eggs will drift away on the currents to develop. The terminal-phase male with the bright yellow saddle maintains territories, the most favored of which are down-current reef prominences where spawning tends to take place.

These males will mate with individual females at the apex of their spawning rush toward the surface, where their gametes are released. The initial-phase males often try and pair spawn with other females at this time when the terminal-phase male is occupied and some even may try to interfere by intercepting the pair at the apex of their rush. The terminal male’s aggression is primarily directed toward these males and neighboring terminal males. Should the terminal male die or otherwise disappear, the dominant individual in the aggregation swiftly takes on his duty and may switch sex (about 30% of the time) to replace the terminal male—a process that is apparently completed in two to six weeks.

Cortez rainbow wrasses feed on zooplankton and hard-bodied invertebrates, as well as small shrimp and fish eggs. The smaller ones sometimes clean larger fish. At night they find shelter in crevices and caves in the reef.

For more information:

Fishbase

The Red List

Animal World

FAMILY: Lutjanidae

FAMILY: Lutjanidae

COMMON NAME: Pacific Dog Snapper – Pargo prieto

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Lutjanus novemfasciatus

Description

Members of the Family Lutjanidae are predators. Their name derives from a Malay name for a fish: ikan lutjan. The dog snapper is one of the larger predatory fish in the Gulf of California ranging up to 170 centimeters (5.5 feet) and 100 pounds (45 kilograms). Males and females are alike. They are truly fearsome-looking: clad in shiny silvery scales, they sport 9 vertical bars, which are more or less pronounced, according to their mood.

Range & Habitat

Dog snappers are a tropical Eastern Pacific species, ranging from the Gulf of California in the north to the Peruvian-Ecuadorian border in the south and the Galapagos Islands. They are a coastal species living over rocky or coral reefs to the depth of around 200 feet (60 meters) and may enter brackish water habitat such as mangroves and estuaries to hunt and forage.

Natural History

They are among the top predators on the reef and may range far beyond the borders of the Cabo Pulmo National Park. Dog snappers are known to be opportunistic hunters consuming prawns, crabs and other benthic crustaceans as well as croakers and fish species such as the schools of grunts and snappers with which they associate at Cabo Pulmo—a habit that clearly makes everyone else nervous.

For a number of important reasons, dog snappers have been heavily fished wherever they occur. All snappers tend to be social, and these are no exceptions. They will hang around in groups, sometimes out in the open water above the reef in specific areas, as they do at Cabo Pulmo, and other times in caves. Additionally, dog snappers aggregate to spawn at specific periods during the lunar cycle in certain months of the year when they will spawn at very specific times of day.

Once fishermen locate these local concentrations, they return to harvest them in the same spot until there is none left. A large area, from which the aggregation recruits, may also be depleted. Finally, dog snappers are particularly vulnerable because they are slow to mature, taking some 14 years to double their population. Despite all that, it has been recorded that in the 10 years following protection by the National Park between 1999-2009, this species saw a 100-fold population increase! While this might indicate that some dog snappers had been added to the population recruitment of young fish, it might also mean that some have migrated into the area and now preferentially use the Park as a refuge.

Cabo Pulmo is one of the few places in the Gulf where one can still regularly see groups of these magnificent fish hanging together during the day.

For more information:

Fishbase

SCRFA

FAMILY: Lutjanidae

FAMILY: Lutjanidae

COMMON NAME: Yellow Snapper – Pargo amarillo

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Lutjanus argentiventris

Description

Yellow snapper may reach 28 inches (71 centimeters) in length and weigh 28 pounds (13 kilograms). Individuals are still relatively small at Cabo Pulmo, as they are perhaps still recovering from overfishing. The adults have a greyish colored head (some even say rosy colored) merging to bright yellow coloration toward the tail and a silver belly. Males and females look alike. They use their tail primarily for propulsion.

Range & Habitat

Yellow snappers are confined to the Eastern Pacific ranging from Baja California south to northern Peru and as far west as the Galapagos Islands. This spectacularly beautiful species of snapper aggregates over rocky outcrops during the day in several locations around Cabo Pulmo National Park. Also, they may spend the day in caves in small groups. They are a coastal species, tolerating water with low salinity and, for this reason, may be found among mangroves. Their schools often mix with other aggregations of nocturnal species such as the graybar grunt (Haemulon sexfasciatus) and the Catalina (Anisotremus taeniatus).

Natural History

Yellow snappers are nocturnal feeders so their daytime aggregations make them a target of local fishermen. Their populations on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs were reduced by the mid-1980s, according to researcher Antonio Villarreal Cavazos. Subsequently, it has been recorded that in the 10 years following protection by the National Park, between 1999-2009, this species saw a 55-fold population increase!

At night, yellow snappers head out to forage over sand and other soft substrates, hunting for other small species, crustaceans and mollusks. They appear to spawn in the spring through the fall with peaks during certain months.

For more information:

Fishbase

Discover life

Encyclopedia of life

PLOS

FAMILY: Serranidae

FAMILY: Serranidae

COMMON NAME: Leopard grouper – Cabrilla rosa

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Mycteroperca rosacea

Description

Members of the Serranidae are comprised of around 450 species worldwide, primarily in the tropics and subtropics, to include the grouper, sea bass and the tiny basslets. Species in that family can range from small, plankton-eating fish such as the Pacific creole or sandia (Paranthias colonus)—common in the Gulf—to enormous sizes such as the Goliath Grouper (Epinephalus itajara) that weighs 800 pounds (362 kilograms) with lengths up to 8 feet (2.5 meters), that are rare, in part because of fishing pressures. Each species is adapted to catching different prey. Leopard groupers are the most common species in the Gulf of California and they, like the rest of their genus, are primarily fish eaters. Their generic name Mycteroperca derives from the Greek mykter, meaning nose, and perke, meaning perch-like. They have a relatively large head and fins with a powerful broad tail for propulsion. They are cryptically colored brownish-green with reddish and pale-colored spots and stripes for camouflage. Approximately 5% of the leopard grouper population has a brilliant xanthic (yellow) color form. They grow as large as 3 feet (100 centimeters) and may weigh 25 pounds (12 kilograms).

Range & Habitat

Leopard grouper are a Mexican endemic species that have increased in population on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs to become one of the most common species once again. Their preferred habitat is over rocky areas to the depth of 165 feet (50 meters). This near-shore habit and their spawning aggregations made them an important target for fishermen around Cabo Pulmo where they were vigorously harvested.

Natural History

The adults prefer fish such as flatiron herring (Harengula thrissina) and anchoveta (Cetengraulis mysticetus) when available, but like all opportunistic predators, they take whatever prey is available or which presents itself. When herring and anchovies are not in season, they hunt small schooling fish (such as Chromis atrilobata), non-schooling fish and crustaceans. They are ambush predators, lying in wait and accelerating swiftly to high speeds for short bursts to capture unsuspecting prey. Leopard groupers are primarily crepuscular hunters and can be observed strategically positioning themselves en masse in the hour before nightfall. Peak hunting activity occurs some 20 minutes after sunset. In daylight, during the sardine migration, they aggregate under rocky overhangs, from which they will launch a coordinated feeding rush toward the surface, snagging their prey before splashing noisily back into the ocean. They also hunt in association with Panamanic green moray eels (Gymnothorax castaneus), prowling under the reef, snapping up fish flushed from cover.

Leopard groupers aggregate to spawn at specific locations that fishermen target. Fishing out a spawning aggregation can decimate a large area. In the mid-80s this species became scarce at Cabo Pulmo. Between 1999-2009 it appears that populations increased only marginally. Fortunately, the Cabo Pulmo National Park would appear to be large enough to protect both the presumed spawning aggregation sites and their habitat, which may account for their resurgence today. They are now common at Cabo Pulmo. Elsewhere in their range the IUCN Redlist identifies leopard groupers as “vulnerable” with a decreasing population.

For more information:

Fishbase

The Red List

FAMILY: Carangidae

FAMILY: Carangidae

COMMON NAME: Bigeye Trevally – Jurel ojon

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Caranx sexfasciatus

Description

Bigeye trevallys are the most numerous of the large predators associated with Cabo Pulmo’s reefs and schools can number several thousand individuals. They have been reported to grow as large as 4 feet in length (120 centimeters) and weigh up to 40 pounds (18.6 kilograms), although at Cabo Pulmo most rarely exceed much more than 3 feet. Their generic name Caranx is derived from the French name for a Caribbean fish: Carangue. Their specific name, sexfasciatus, means 6-banded, referring to the markings on juveniles of the species. Bigeye trevallys, streamlined and oblong in shape, have compressed bodies. They have large eyes for nocturnal vision with what are described as adipose (fatty) eyelids. Their bodies are covered in fine scales that range in colors from olive and blue-green on the back to silvery white on the belly. Their characteristic black spot just behind the gill cover (operculum) and white tip to the front lobe of the second dorsal fin are distinctive. Also characteristic of this species are the 27 to 36 bone-like scutes running along the lateral line from the mid-body to the tail.

Range & Habitat

This species is an extremely successful tropical resident, ranging across the entire Indo-Pacific from the Red Sea to Mexico. Their schools are iconic features of Cabo Pulmo National Park. This species is primarily confined to coastal areas and around offshore islands, but may also be found around seamounts in open water. Bigeye trevallys frequently forage in the shallows as the tide rises and the young are found along beaches, in mangroves and in estuaries. Adults move freely between fresh and salt water and they may even penetrate far upriver. As the young develop, they move away from the shallows and into deeper waters.

Natural History

Bigeye trevallys are primarily nocturnal hunters. During the day they gather in schools for protection over reefs and at night scatter to feed alone throughout the upper 300 feet of the water column, primarily on other fish. They have a wide diet that also includes planktonic life forms such as copepods and salps, squid, larger crustaceans, mollusks and even sea-skaters (marine insects). In turn, bigeye trevallys are important prey for larger jacks, tripletails, sharks, sea lions and seabirds.

When the water temperatures exceed 28 degrees centigrade, these animals will breed. It is said that this occurs primarily around new moons. Within the school, individuals will pair. One of them (presumed male) closely tracks its mate and will switch to a darker color instantaneously and then, following an interval, the pair may peel away from the school to spawn. The eggs are scattered into the water column and carried away with the plankton. As the larvae and young fish increase in size, they graduate from a diet of insects and planktonic crustaceans to other fish. Following the larval stage, many of the young end up in estuaries or in freshwater, a tactic likely to reduce predation. There is a cost to this strategy; freshwater habitat is less calorific than marine habitat is. Consequently, the young fish in such locations may grow more slowly. Eventually, all will head back out into salt water (anadromous) to live most of their adult lives at sea. It has been recorded that in the 10 years following protection by the National Park between 1999-2009, this species saw an 8-fold population increase.

For more information:

Fishbase

Research Gate

FAMILY: Carcharhinidae

FAMILY: Carcharhinidae

COMMON NAME: Bull Shark – Tiburón chato

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Carcharhinus leucas

Description

Requiem sharks, in the genus Carcharhinus, are named for the Greek karcharos, meaning sharpen, and rhinos, meaning nose. The ubiquitous bull shark defies this primary family characteristic. In contrast to other requiem sharks, the bulls are distinguished by having thick bodies, broad, blunt snouts, small eyes, triangular saw-edged upper teeth, and blunt dorsal fins situated forward of the midline of their bodies. They also get very big. The females are larger than the males are, topping 13 feet (4 meters), and may weigh 700 pounds (320 kilograms).

Range and Habitat

The bull shark is an amazingly successful species that ranges globally throughout the tropics and subtropics in coastal waters to depths of 500 feet (150 meters). These sharks have a broad temperature range from latitudes 42 degrees north to 39 degrees south. They can tolerate long periods in fresh water and have been recorded 2,000 miles upstream from the mouth of the Amazon River in the region of Manaus, and are recorded in Lake Nicaragua.

Natural History

The bull shark’s primary prey is fish (such as rays, ladyfish, mackerel and mullet), squid, prawns and the occasional turtle. The sharks also forage for carrion, particularly in bays and along beaches where prevailing winds concentrate food floating in the ocean. This habitat just happens to coincide with concentrations of people: where we swim and fish, where we frolic in the waves and boat. The bull shark is frequently said to be the most dangerous species for people for these reasons.

For divers, it is usually extremely difficult to get close to all species of sharks without enticement. They have been around for more than 400 million years and have survived in part because they are cautious. However, the distressed movement of a fish in trouble immediately excites them and, if one is spearfishing, they can become aggressive. Additionally, when a shark sees only part of a person—a leg in the shallows or one hanging innocently from a surfboard—it may, on occasion, test how it tastes. Sharks rarely follow up on such an attack, leading to a conclusion that such an incident may be unintentional because they may be unaware of exactly what it was they were attacking. In 2015, there were less than 100 shark attacks globally and there were only six fatalities. On the other hand, in the United States alone, lightning kills 33 people and injures approximately 300 more annually. According to a Florida University study, one’s chance of being attacked by a shark is less than one in 2.9 million.

On the romantic side, bull sharks mate, male to female, in a distinct embrace. The female will carry her young that develop viviparpously—that is, with a yolk-sac placenta nourishing the embryo—and there is a gestation period of 10-11 months. She will produce a litter of up to 13 live young, usually in spring and early summer (although in parts of her range, year-round).

For more information:

Fishbase

The Red List

Discover LifeUF News

Florida Museum of Natural History

Taronga

FAMILY: Labridae

FAMILY: Labridae

COMMON NAME: Mexican hogfish – Vieja de piedra

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Bodianus diplotaenia

Description

Mexican hogfish have all the characteristics of a typical wrasse (Labrid).

Characteristics include a large head, prominent teeth, particularly on the lower jaw, and large lips. Mexican hogfish have protractile mouths enabling forward movement and pharyngeal teeth (these are believed to be modified from the gill arches of early fish that did not have mouths) for crushing animals with shells. Their bodies are deep and moderately compressed laterally. They swim primarily using their pectoral fins, unless they require a burst of speed at which time they use their broad tail (when pursued by a predator, for example).

Their scientific name derives from Portuguese words bodiano or pudiano, meaning modest, from the Greek diploos, meaning two, and tainia, meaning ribbon. The young are bright yellow early in life with two dark stripes extending through the eye along the upper part of their bodies to end as two dark spots on the yellow tail. This pattern may reference the tainia (ribbon) in their name. However, the brightly colored terminal-phase males have long, ribbon-like streamers on their dorsal and tailfins. They may grow to a size of 2.5 feet (76 centimeters) and weigh as much as 20 pounds (9 kilograms).

Range and Habitat

Mexican hogfish are found as far north as Guadelupe Island off the coast of Baja California, throughout the Gulf of California and southward to Chile. This wrasse is one of the more abundant species on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs. Mexican hogfish live in shallow, inshore waters to the depth of 250 feet (around 75 meters). They prefer rocky outcrops and coral reefs, often with interspersed sandy areas, where they forage primarily.

Natural History

Mexican hogfish are diurnal, more or less solitary, although they are sometimes found in small groups, gathering at sources of food. Juveniles will gather at “cleaning stations,” where they perform the all-important job of grooming other fish that submit to their attention. At night, they must find shelter, either among rocky caves or buried in the sand.

Mexican hogfish are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning that all the young are destined to mature as fully functional females. Then, for reasons not yet fully understood, but quite likely due to a change in the social structure of others in their home range, an individual may switch sexes. The terminal-phase males develop large bumps on their foreheads and long, flamboyant streamers on their dorsal (top), anal (bottom) and caudal (tail) fins. Their coloration turns greenish or pink and they are marked midsection by a broad yellow band. During breeding periods, the males are said to defend territories called leks and will pair with females that approach, together scattering the eggs and milt over the seafloor.

These fish are important predators on Cabo Pulmo’s reefs, consuming all kinds of invertebrates such as mollusks, sea urchins, crabs, shrimp, worms and other small fish. In fact, when the number of these and other predators of invertebrates are reduced by overfishing, the reefs may become dominated by sea urchins. An abundance of the latter is an unfortunate indication of overfishing.

For more information:

Fishbase

The Red List

Discover Life

FAMILY: Haemulidae

FAMILY: Haemulidae

COMMON NAME: Graybar grunt – Burro aimejero

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Haemulon sexfasciatum

Description

It is a handsome, silvery fish with yellowish-colored flanks marked by six vertical grey bars.

Range and Habitat

The graybar grunt is a tropical species native to the Eastern Pacific Ocean ranging from Bahia Magdalena (Baja California) and the Gulf of California to Ecuador, including Galapagos and Malpelo Islands. While these grunts have been reported to reach 28 inches (71 centimeters) in length and weigh five pounds (2.3 kilograms) around Cabo Pulmo, they are more commonly around 12 inches (30 centimeters) in length. Graybar grunts are a commercial species of minor importance (usually harvested as bycatch), but they are considered excellent eating and are often caught for personal consumption or for fish bait.

Natural History

Graybar grunt are nocturnal, gathering over Cabo Pulmo’s reefs during the day to form large inactive schools. At night, the schools disperse and individuals forage for fish, crustaceans, mollusks and echinoderms, often by digging in the sandy areas surround the reef.

Graybar grunts breed by pairing and scattering eggs over the seafloor. Being buoyant, the eggs are dispersed away from their point of origin in the currents. Beyond these facts, there is remarkably little knowledge about this species, or indeed the entire family of grunts. Following their protection in Cabo Pulmo, their numbers increased 3-fold.

For more information:

Fishbase

Mexfish

FAMILY: Serranidae

FAMILY: Serranidae

COMMON NAME: Gulf grouper – Baya or Garropa

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Mycteroperca jordani

Description

Gulf groupers grow to a length of 6.5 feet (190 centimeters) and may weigh 200 pounds (91 kilograms), making them highly attractive catches for both artisanal and sport fishermen. They are typically dark brown or greyish in color but can change in an instant (into their juvenile coloration) when stressed, disturbed or otherwise aroused. They are late-maturing fish (females 6 years) and are long-lived (48 years). Large adults have a white margin on their pectoral fins. They have huge mouths and heads, deep bodies and large fins. When undisturbed, they move effortlessly about the reef. They are ambush predators that use their broad, powerful tails to launch themselves at high speed, vacuuming their prey with their large mouths and backward-pointing teeth.

Range and Habitat

The Gulf grouper is almost a Mexican endemic within the subtropical distribution in the Eastern Pacific Ocean ranging from La Jolla, California (32.84° N) throughout the Gulf of California to Mazatlan (23.22° N) in the south. It is likely that the La Jolla animals are derived from a Mexican breeding population. There was an ostensibly reliable report of a single specimen in a Panamanian fish market (with no information about where it was taken). Typically, Gulf groupers reside around rocky reefs in relatively shallow water and to the depth of 148 feet (45 meters) in summer.

Natural History

Gulf groupers are among the most charismatic species to be found at Cabo Pulmo. They are primarily piscivores, meaning fish-eaters, and they appear to hang around schools of likely candidates. They have been reported to eat young hammerhead sharks and are known to hunt crustaceans such as slipper lobsters (Scyllarides astori).

Decades ago, overfishing reduced their numbers in the southern Gulf of California where they are still rarely encountered by divers today. Cabo Pulmo is the notable exception, where their population is still recovering. It is reported that they are more frequently encountered in the northern Gulf, although they are still uncommon there. At one time, the local fishermen believed that this grouper’s growing scarcity was due to the fish moving into deeper water. This may be true for part of the year, as scientists report that they may move into deeper water in summer. In winter, they can found in shallow water, primarily associated with rocky reefs and kelp beds.

It is believed that since fishing began, gulf grouper populations have been reduced to less than 1% of their historical levels (circa 1940). Part of this may be due to the fact that Gulf grouper are protogynous hermaphrodites (they start life as a female and only later in life may change sex). Since males are older and larger, they may be preferentially selected by fishermen, thereby skewing their sex ratios and adversely affecting breeding success. Before, during and after the full moon in May, Gulf groupers have been observed in aggregations, behaving in ways that other members of the same genus behave when spawning—by flashing color changes. Spawning aggregations make them particularly vulnerable to overfishing because they occur repeatedly at the same location, at specific times, year after year, which fishermen learn about and target.

By contrast, at Cabo Pulmo today, Gulf groupers are very much in evidence. Scientists recorded that in the 10 years following protection by the National Park, between 1999-2009, this species saw a 15-fold population increase!

For more information:

Fishbase

The Red List

Research Gate

Sala, E., Aburto-Oropeza, O., Paredes, G., Thompson, G. Spawning Aggregations and Reproductive Behavior of Reef Fishes in the Gulf of California. Bulletin of Marine Science, 72(1): 103–121, 2003.

Additional information about other fishes of the Gulf of California may be located on another website of a Summerhays Films production: Ocean Oasis